“It’s like poetry, sort of – they rhyme” may be one of George Lucas’ most lambasted quotes, but there’s more to the cinematography and philosophy of the Star Wars movies that many casual film-goers realise.

Having been produced in different eras and against different political backdrops, each of the Star Wars trilogies in the ‘Skywalker Saga’ explore different conceptions of morality, building on each previous trilogy’s lore and contextualising the ideas presented in earlier installments.

Meanwhile, the ‘poetry’ of the cinematography which Lucas, the franchise creator, spoke about is the use of visual cues and similar shots to establish familiarity and evoke scenes in other films, maintaining a cohesive visual identity while encouraging viewers to think about similarities, differences and consequences of actions between the separate trilogies.

The Original Trilogy

Written in part as a response to the injustices and shallowness of the Vietnam War, the original Star Wars trilogy – consisting of classics A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi – presents a simple black and white morality of good versus evil.

Though the Sith are only introduced by name in the prequel trilogy, the Jedi – users of the light side of the force – are seen as guardians of peace, the galaxy having been thrown into disarray and despair after the rise of the Empire.

The Empire is a plastic representation of evil, its political ideology – besides from destroying planets which don’t comply to the Emperor’s rule – unexplored to ensure there’s no ambiguity of morality.

The figureheads of the Empire themselves – the Emperor (he is only christened Palpatine/Darth Sidious in the prequels) and Darth Vader are similarly cardboard cutout. Though Vader does get some character development in Return of the Jedi and is often read as a metaphor for the mechanization of war (and, in more recent times, a symbol for the thinning boundaries between people and technology), most of these ideas about the character have their genesis in the oft-lauded prequel trilogy. In the originals, Darth Vader is still pretty badass, and serves for the most part as a simplistic and highly tuned symbol of faceless evil.

The moral here is clear: some ideologies are good, others are evil – of course, we don’t see here the politics of either the Empire or their competitors, the Rebellion. History is told through the eyes of the victors but, by following the analogy of the Vietnam War, could it be said that the Rebellion is actually Vietnam? Using outdated technology and rag-tag methods of warfare (most famously in the Battle of Endor in Jedi), what was left of the Republic managed to shake free from the shackles of a highly advanced, wealthy and technologically and resource-driven Empire. Remind you of anywhere? And no, we’re not talking about Disney.

While no doubt the easily digestible presentation of classical binary morality no doubt adds to the original trilogy’s timeless appeal, future iterations of the franchise called into question the effectiveness of dividing the world into the good and the evil – the dark side and the light side – and suggests we should look at the world through a more critical and open-minded lens.

The Prequel Trilogy

On the surface a continuation of the binary morality found in the original trilogy, The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones and the (quite frankly brilliant) Revenge of the Sith do much to ensure the surface view of the Jedi as good, the Sith as evil continues – only to shatter this binary in its subtext.

Here, we see the final days of the Republic. First suggested as an ideal society in A New Hope, audiences get to see holes in this utopian system. The Republic heaves with corruption and hypocrisy, with Chancellors who overstay their terms, political interference from the Jedi, and back-door deals between shadowy figures and cloning facilities to create armies.

Emperor Palpatine’s rise to power is as much a cautionary retelling about Hitler’s rise to power (note the obvious Nazi imagery throughout all the movies) as it is a criticism of flawed electoral systems, and how democracy can easily be hijacked by members of the Far Right or Left. “So this is how liberty dies,” Padme says, lamenting Palpatine’s grasp of emergency powers. “With thunderous applause.” Meanwhile, the Separatists are seen by the Republic as shallowly evil as the Empire is presented in the original films, while many of the systems desire independence from the heavy taxation imposed on them by the Republic.

The Jedi Order is hardly given less scrutiny. Anakin’s ‘fall’ to the dark side is often mistaken as a simple and silly move to learn how to save his wife from dying in childbirth, but throughout the trilogy Lucas pulls no punches when it comes down to criticising the Jedi order, Anakin often being the victim of some of their more questionable acts.

Children are torn away from their families at a young age, taught not to love and to have no attachments. They’re groomed to be fierce warriors, convinced that they are responsible for keeping the galaxy in order, while also acting as an unelected body with heavy political influence.

Anakin expressed his disillusionment with democracy as early as Attack of the Clones and, having faced criticism after criticism from the very order which alienated him from his family, it was only natural he would gravitate to the person who always accepted and supported him: Palpatine.

Although it’s not part of this trilogy, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, which is also a prequel to the original films, complicates the black and white morality further by showing supposedly ‘good’ characters – members of the Rebellion – doing questionable things, such as shooting injured comrades for an easy escape. Ideologies might be presented as perfect, but individual soldiers in war never are.

The Sequel Trilogy

Here’s where it starts to get complicated. Although other writers and directors helped out for The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, the original and prequel trilogies were both Lucas’ brainchild. The sequels, meanwhile, are the works of different writers and directors with dubious reports about whether an overarching story was agreed in advance, raising interesting questions about art, authority and ownership. Things are further complicated by the fact that the last movie in the Skywalker saga, The Rise of Skywalker, has not yet been released. However, The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi still present some interesting and (whether by design or not) cohesive ideas about morality and heroism which expands on the lore of Lucas’ trilogies.

If heroes had been wounded in the prequels, the sequels are where they went to die.

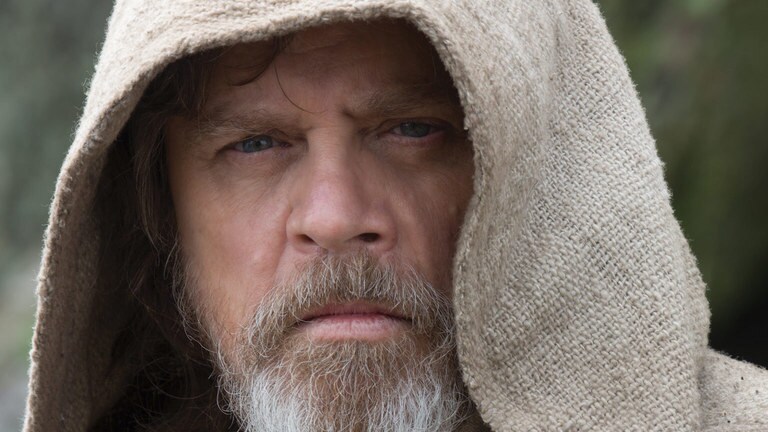

Rian Johnson faced much criticism of his presentation of Luke Skywalker, the golden and untarnished symbol of heroism and everything good in the original trilogy, in The Last Jedi. He appears disenchanted with the Jedi order, learning – as audiences did in the prequels – that the hubris of the Order led to the rise of Palpatine, and that “to say that if the Jedi die the light dies is vanity”.

Not only is this presentation of Luke consistent with JJ Abrams’ in The Force Awakens (Johnson had to justify why Abrams would have Luke hiding on a remote planet), it is also consistent with lessons learned in the prequel trilogy.

Kylo Ren, this series’ Big Bad, can be read as an inverse of Anakin Skywalker, feeling a pull toward the light side just as Anakin felt a pull toward the dark. While Anakin/Vader wore a mask due to physical defects, Kylo’s costume is indicative of another of the sequel trilogy’s main themes – hero worship.

In The Force Awakens, we learn that ordinary people such as Rey (*subject to retconning) see famous Star Wars symbols – Luke Skywalker, the Millenium Falcon – as myths, mirroring the perception of the franchise in the real world. Symbols for hope and good, which must not be interfered with or complicated. However, refusing to criticise our heroes and taking a one sided, narrow-minded approach to the world and our views, can lead to harm. The Jedi Order, the keepers of the light, damaged the galaxy precisely because so many people had faith in them.

How Kylo and Rey’s storyline will end will no doubt flesh out the ideas of the sequel trilogy even further, though already they have both been seen to neither comply strictly to the old binaries of the light or dark sides of the force. There is good in Kylo, as there is the potential for evil in Rey – and Luke’s refusal to see conflicting emotions and ideas as anything other than pure evil almost led to him killing his own nephew in a state of puritanical, Spanish Inquisition-esque ideological cleansing.

By complicating the good/evil binary found in the original trilogy, both the prequels and the sequels lost some fans who were expecting a continuation of the simplistic and un-nuanced fairytale narrative of A New Hope. But the world is complex, and in a world saturated with increasingly simplistic political slogans, necessitates now more than ever being viewed through complicated and critical lenses.

In the words of Obi-Wan Kenobi in Revenge of the Sith, “Only a Sith deals in absolutes.” Which is precisely what the Jedi were doing the whole time, too.

Matteo Everett

[…] in a way no movie had since The Phantom Menace, focussing on more intimate narratives and taking inspiration about ideas and notions of heroism from Rogue One. Killing Snoke was a stroke of genius, and we can only hope that Abrams decides to use Rian […]

LikeLike

[…] wouldn’t go amiss. The species was introduced in the first episode of the Saga and Star Wars is all about symmetry, after […]

LikeLike